Sunday, May 10, 2009

Making A Difference...

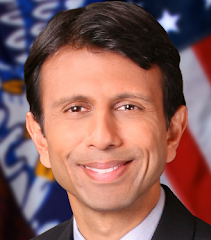

Bobby Jindal is many things. He is an intellectual; he is a politician; he is the son of immigrants and most importantly to me, he is an Indian. Ever since I can remember, Indians have been praised for their intellect, but never the less, have been thrown under the bus by their superiors because of their color; especially in Brittan and until now in the

Bobby Jindal Essay

Bobby Jindal, only the second Indian American to serve in the U.S. Congress, has a resume as impressive as some politicians in their 60s or 70s. Yet Jindal was only 33 when he became a congressman. By then, he had already run for governor of

Jindal was born in 1971 in

In 1996, at age 24, the new governor of

State legislators thought he would be totally ineffective. The job seemed impossible for anyone. The department, which took up 40 percent of the state budget, was running a deficit of $400 million. The federal government was investigating its administration of federal Medicaid funds. But within three years, Jindal had turned the department around, exposed millions of dollars of waste and fraud, and eliminated its massive deficit. (Wall Street Journal; 1998)

Jindal discovered that the state paid lump sums to hospitals at the beginning of a year based on how many Medicaid patients they estimated they would treat, but the state was rarely checking to see if they really treated that number. He discovered clinics that employed a dozen people but had no patients, even a clinic that bused in schoolchildren to receive candy instead of care. (Washington Post; 1998)

Meanwhile, Jindal earned a reputation for honesty and frugality by buying a car instead of accepting a government vehicle, by talking in simple terms about politics in front of the legislature, and even, when he got married to Supriya Jolly, he asked ethics officials how he should handle wedding presents from people he might regulate, then including that advice in his wedding invitations. (Esquire; 2003)

After his success with the health and hospitals department, Jindal returned to

After that series of dazzling career moves, Jindal decided to add one more. In 2003, he ran for governor of

Though Jindal led in many polls before the election, Blanco beat him 52 to 48 percent. Within months of the election, Jindal announced that he would run for Congress, hoping to claim a seat that would open up thanks to the departure of a Republican congressman. Jindal fit the conservative bent of the district, which includes suburbs of

Reporters found Jindal eager to talk about health care reform, even though congressional leadership did not name him to a health care committee. With health care costs and the number of uninsured people rising, Jindal insisted that Republicans needed a positive vision of health care reform. Of course, his status as the only Indian-American congressman got him attention, too. News services in

On January 14, 2008, Jindal was elected the 55th governor of

1. AP Online, July, 2005/ November, 2008

2. Esquire, December 2003

3. Gannett News Service, July, 2005/ July, 2005.

4. Hill, September, 2005

5. National Journal, January, 2005

6. New York Times, January, 2004

7. Time, October, 2003/ September, 2005

8.

9. Wall Street Journal, January, 1998

10.

11. Weekly Standard, December, 2004

- http://jindal.house.gov

- www.bobbyjindal.com